“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

Bolts create a negligible ecological impact, especially compared to lands that have been entirely taken for cities, urban sprawl, sports fields, reservoirs, logging, and oil and gas production. Despite the extremely low ecological impact of bolts, they do create a visual impact. When other user groups see shiny bolts, they may form a negative opinion about climbers. “How come they get to leave trash in the wall but we’re not allowed to drive on this road anymore?!” In some cases, they complain to the land managers who write the rules.

Sure, many of us would agree that bolts have less of a visual impact than trails, interpretive signs, roads, pit toilets, trash cans, and power lines. Others may assert that “less bolts is more badass.” But I’m not here to talk about the style aspect of bolting.

Nearly 40% of the United States is public land. While this land is “ours,” various agencies manage and regulate it. These agencies include the National Parks Service (NPS), National Forest Service (NFS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), state parks, county parks, and city parks. Some agencies were created to conserve the land, meaning they allow a wide variety of users to share the land cooperatively, while minimizing wear and tear. Others (mainly the NPS), exist to preserve the land, essentially ensuring it largely remains in its natural state.

Whatever the public land, whatever the agency managing it, reducing our impact means less wear and tear. It also keeps the area in a more “natural” state. Could painting bolts help us do just that?

Why painting bolts matters

When climbers push their luck and make too much of an impact on public lands, land managers step in. One of the first courses of action they take? Bolt restrictions and bans. I have borne witness to this firsthand. In 2024, the NFS asked me to lead a large bolt removal project, spawned because of this very issue. In 2015, the NPS asked me to speak at a meeting where they pondered strict bolting regulations at my home crags. This type of story is painfully familiar to anyone who looks behind the curtain of climbing access.

When climbers have too much impact or become a nuisance, access becomes threatened. Then we must ask the already-busy Access Fund to help bail us out. After all, most of us are just trying to go climbing and not worry about how access can be threatened by social trails, parking, poop, excessive tick marks, permadraws, and overly shiny bolts.

Don’t worry, though: It’s not all doom and gloom! Maintaining access to bolted routes is actually not that big of a deal. In my many conversations with countless land managers and Tribal members over the last 10 years, I’ve learned that what these groups care about most is respect. If we can be the best stewards of the land, we can sometimes have metal in the rock. An important part of respecting the land is to make this metal blend into the rock and the landscape. Nothing says f*** you to the land managers and Tribes like shiny metal visible from hundreds of yards away.

One example of this went down this winter in Indian Creek, which is part of Bears Ears National Monument. In January, the Bear Ears National Monument Resource Management Plan went into effect. This new plan requires a permit for all new routes and requires all new bolts to be painted to match the rock.

In other areas, like Canyonlands, bolting routes is all but banned with strict permitting requirements. This is despite that fact that non-climbers are unlikely to even notice the bolts. If bolts were less visible, maybe challenging permit systems and outright bans wouldn’t exist. It’s far less common for people to be affected by what they can’t see.

“I can’t see the bolts!” (Yes, you can.)

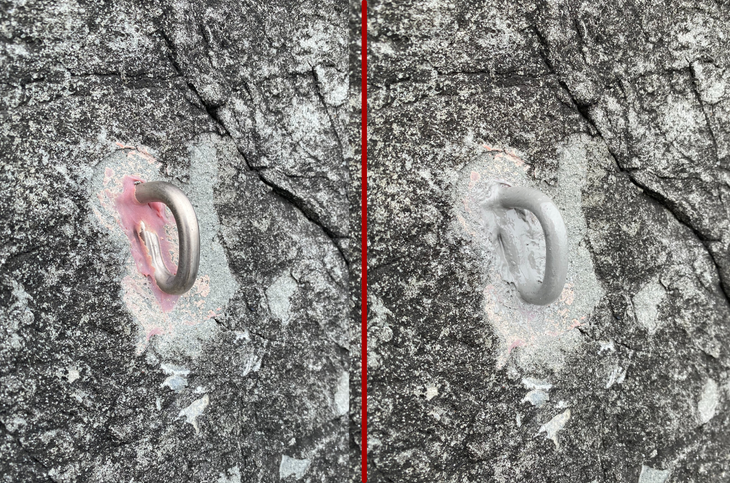

Paint doesn’t magically make the bolts disappear. But the lack of sparkle does make them much harder to spot accidentally, or from far away like a hiking trail or road. Rest assured, climbers: Anyone hiking at the base of a cliff and looking up to find bolts will undoubtedly spot them. They are, after all, a 3D apparatus protruding from the wall, often casting a shadow.

In Indian Creek, climbers often use plaques to help climbers find routes. Additionally, I highly recommend that route developers publish high-quality photos and descriptions of the route’s location in guidebooks and on Mountain Project. This allows climbers to find routes by following natural macro-features, rather than looking for the unnatural arrow of shiny bolts. Posting routes and photos on Mountain Project also prevents accidental retrobolting.

This is much preferred over shiny so-called “fuck off anchors.” At least one developer in Indian Creek promotes using shiny anchors that are visible from the road in order to ensure that nobody adds lower anchors onto their route. My response to this is that if you’re scouting for new routes, you’re likely also using binoculars or telephoto lenses to ensure the route doesn’t have anchors. Painted bolts are always visible upon this closer, purposeful inspection. If routes are well documented and still sprouting anchors, something else may be going on.

When you’re actually climbing, a painted bolt is rarely any harder to spot than a non-painted bolt. Spotting bolts while climbing comes with experience. If you can see the crimp, you can see the bolt. After developing 590 pitches on several dozen rock types, I have found that bolt spacing, 3D rock texture, or a bolt hidden behind a feature is almost always the reason why a bolt is not readily visible. Painting the bolts makes little difference to the climber’s experience, aside from making the route look less like a gym. When the bolts blend in, route developers can feel more comfortable adding a few extra bolts without feeling like they’re increasing their impact. This, in turn, can make the routes safer with more attentive bolt spacing.

Of course, there are caveats to everything. It can be unnecessary to camouflage anchors deep in the alpine. If there aren’t any hikers for miles, blending your bolts in is definitely less important. Consider, however, that not all bolt-lovers love to see bolts shining from afar. When I walk up to a cliff, I want to see a beautiful natural cliff, and then for the bolts to reveal themselves as I come closer. Land managers will see the routes eventually. Wouldn’t it be cool to impress them with your respectful attention to detail?

So how do you paint a bolt?

Prepainted hangers offer a convenient start. But these hangers don’t always match just right and still leave the bolt head and anchor material to be painted. Keep in mind that most painted hangers are actually plated steel, not stainless steel.

To paint a bolt before installation, poke the assembled bolts through a cardboard box, and apply many thin coats of spray paint primer. Lay anchor material flat, and rotate after drying to paint all surfaces. Don’t worry about accidentally painting where the rope will run—the rope will quickly and harmlessly rub that off. Thinner coats dry easier and stick better. Thick coats will peel off.

After priming, apply several different colors. Try to match the rock color in your area. Use matte spray paint in short, thin bursts until you’ve reached the desired result. Be careful when transferring the bolts. Bolts bashing around in a bag on the way to the cliff can scuff up the paint.

If a bolt is already installed, the cheapest method to paint it is taping up the wall. You could also use cutouts for spray painting. This can sometimes be quite a charade—it’s usually my last resort if there are lots of bolts to paint. Please do not paint the actual rock!

My preferred method is more pricey, but very effective. I like to bring a few pieces of the rock into the paint shop, so they can scan the various colors to mix the paint accurately. “Direct To Metal” paint is the best that I’ve found so far, but it is expensive. Our local climbing organization was able to buy a substantial amount of paint and supplies through a grant from Access Fund.

At home, I pour each color of paint into a half-cup tupperware container. Then I climb the route or ascend a rope with the tubs, a small homemade paintbrush holster, and some paper towels and water (just in case). I then lightly and carefully dab (not brush) paint on the bolt with two or three thin coats. Intermixing colors creates textural accuracy. If your paint is too thick, it will drip and peel off after drying. Quickdraws will naturally rub paint off of certain parts of the hanger, and that is okay.

The Wild West days of climbing are coming to an end, more and more land managers are leaning into their role as regulators. If you choose to camouflage bolts, great! If you don’t, don’t worry too much. It’s only the law in some places so far. For me, painting bolts is just part of the route development and crag maintenance process, and I hope it becomes part of yours, too. We, as climbers, can be proactive and maintain a good image to avoid access issues in the future—one painted bolt at a time.