When Cyprien Verseux was told he’d have to undergo some training before he set out to Antarctica in 2019, he thought that sounded reasonable. There are some basics expected of everyone who’s sent to do scientific investigations at one of the research stations in the remote, icy continent: a medical assessment, some basic survival skills, a psychological profile. After a dramatic 1971 incident in which the sole medical doctor at a USSR station had to cut out his own appendix, some countries made appendectomies a requirement for their “winter-over” medical staff in Antarctica. Most others will ask that a dental X-ray is done and wisdom teeth are taken out if it looks like they could impact. That’s because, once you arrive at an Antarctica research station for the winter, you can’t be reached again for nine months. It’s just you, a skeleton staff (most people take the three-month summer option), and perpetual darkness.

That complete isolation from the rest of the world is the reason why everybody there needs basic survival skills. Generators can fail, food can spoil, people get locked out of their accommodation by accident, emergencies happen. Knowing how to cope — and to remain calm — in such situations is just common sense. Verseux knew all of that. He thought it was a good idea.

What he didn’t expect was what happened once the training kicked off. During a week in Italy, stationed at the side of a lake, Verseux and his team — a small group of scientists and the physician who would be traveling with them — were taken out into the middle of the lake in a boat by one of the trainers, who was from the Italian military. “We thought it was to learn how to drive the boat,” he says, “but then one of the trainers… grabbed the medical doctor of our crew and threw him in the water and said: ‘Oh, now you’re saving him.’”

A few days later in the training week, Verseux says, “we were told to go into a building, and they say: ‘OK, you’ll get in and then you’ll react.’ I say: ‘To what?’ ‘Well, react to what you see.’ And then we get inside, and we hear some screams coming from a room in the distance. And so we run, we look for the room where the scream was coming from. And then we see somebody on the ground, unconscious, with blood coming out of his arm and a chainsaw next to him.” Verseux shrugs, matter-of-factly. “Of course, it was an actor, but a very realistic simulation.” Once the group had secured the scene and sent the person for rescue, “we heard some other screaming, from somewhere else in the building.” The pattern continued for a number of hours: We spent half a day running from emergency to emergency.”

The surprises kept on coming. Not long after that test, Verseux says, he and his team were tasked with running through a U-shaped tunnel whose walls were on fire, armed with only a blanket. And after that, he was told to scale a gymnasium, climb through a window, take a ladder up to the roof and then flick certain switches. That, he says, sounded “simple enough” — until the room was filled with smoke so thick he couldn’t see his hand in front of his face.

A lot of the exercises Verseux and his team took part in involved smoke, heat or fire, he says, because “fire is one of the main risks in the station, and you have to prepare for that — both to be able to leave the base if there is a fire, but also to save the base if you can. Because of course, if the base burned, then you’re outside, it can be -80C [-112F], and then you’re in trouble.” ‘Trouble’ is, of course, somewhat of an understatement.

These tests weren’t just designed to test the crew’s reactions and their ability to put theory they’d learned previously into practice, but they were also psychological tests overseen by experts who were choosing who might be best suited to lead the station. A station leader can come from any role and any profile — one year, it might be a Navy officer; another, it might be a communications specialist. Different countries have different methods for selecting their leaders, but on Verseux’s joint French-Italian mission, the decision was made by overseers while the crew prepared to deploy to Antarctica, and the exact criteria for that decision-making wasn’t made known to the crew. At just 27 years old and in the final weeks of his PhD, Verseux was an unlikely candidate. He was surprised as anyone else to find out that he had been selected as leader of the 13-person group just before they set out for the winter.

What probably helped was his calm and measured demeanor. He methodically describes the dramatic battery of tests he went through; the experience, he says simply, was “interesting”. Sometimes, he adds, it involved some logistical juggling, since he was rushing to finish his PhD in astrobiology at the same time. At one point, he turned up for two days’ training at a military hospital, only to find a note in his hotel room that told him to make his way to the other side of the country for a week. So much for his plans to be in the lab at university.

Verseux had originally only applied for the three-month summer stint, doing microbiology research related to his PhD, but he’d been selected for a year-long summer and winter-over doing glaciology instead. He had to convince his professors to allow him to defend his thesis remotely from Antarctica, by satellite connection.

“We had to stop the internet for the entire station so I would have enough bandwidth,” he says, “and even then it was chaotic.” Somewhat unsurprisingly, the connection dropped while he was in the middle of his defense.

A place that belongs to everyone and no one

Although no country owns Antarctica, several nations have made territorial claims on parts of the continent. Those claims are held in check by the Antarctic Treaty System, signed in 1959 and now with 56 parties, which freezes all sovereignty disputes, bans military activity (except for military deemed necessary to help protect civilians undertaking research) and mineral mining, and reserves the region for peaceful scientific collaboration. Seven countries — Australia, New Zealand, France, Norway, the U.K., Argentina, and Chile — have formal claims, some of which overlap, particularly around the Antarctic Peninsula. (Notably, the U.K., Argentina, and Chile all claim the same swath of land.) These claims are not universally recognized, and under the treaty, no new claims can be made.

Many other countries, including the United States, Russia, China, South Africa and India, maintain scientific bases on the continent without asserting ownership. The U.S. and Russia, while not claiming territory, reserve the right to do so. In practice, Antarctica operates as a rare example of international cooperation: a vast, frozen expanse governed not by national borders, but by a shared commitment to science, conservation, and diplomacy.

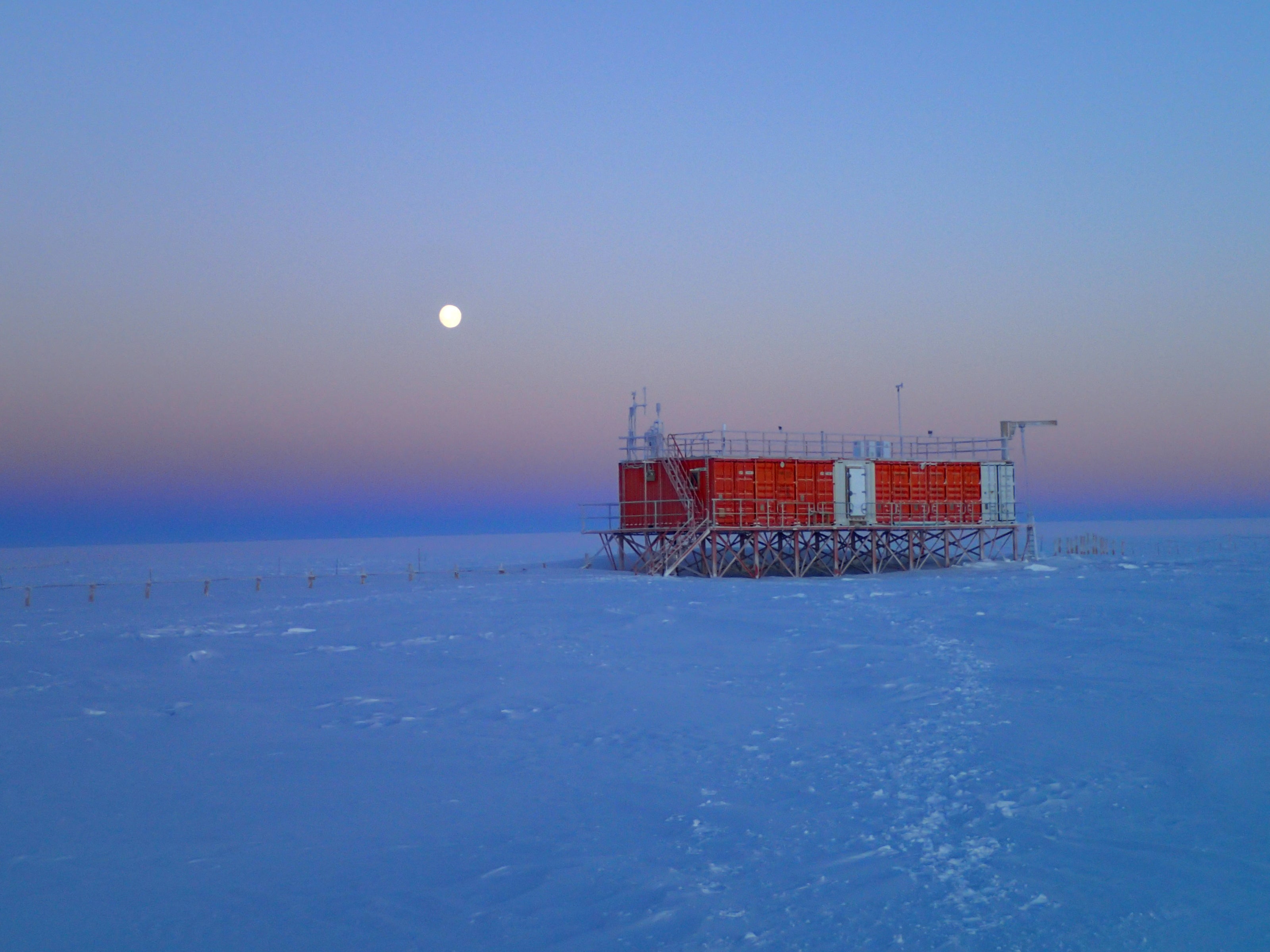

At the remote Concordia station where Cyprien Verseux was stationed — a research facility shared between France’s Polar Institute and Italy’s PNRA, and one of only three based far into interior Antarctica — a maximum of 40 people usually come for the three-month summer period. Once they leave, the station has an even smaller skeleton crew of around 16 people. Verseux’s crew, of course, was even smaller than that.

Among the skeleton winter crew, most work individually, in two separate teams: the technical team (a plumber, a mechanic, an electrical engineer, a janitor, a cook) and the research team (a computer scientist, an astrophysicist, a glaciologist and so on.) Nine months of non-collaborative work in the pitch black in the middle of nowhere with just 12 other human beings would be a challenge for a lot of people.

“Many people hardly sleep” during the 24 hours of sunlight in the summer, he says, “and so there’s always a lot of things going on — until one day in the beginning of February. Then everybody goes away, except the people who stay for the winter-over, and from that moment, we know we’ll be completely isolated because it gets colder and colder, and often it can be down to below -80 Celsius (-112 Fahrenheit). And [in that temperature] planes cannot fly, as all the soft parts will freeze and they would break when they try to land.” As the light fades day by day, there is “a period when you have sunsets and sunrises that follow each other. And then [the sun] goes lower and lower, and then sometime in May, it goes below the horizon for last time, and then for three months you won’t see it at all. Most of the time it’s pitch black — except of course for the stars and the moon, which you see very, very well.”

Did he never find that psychologically challenging, I ask? No, he says. As the sun began to gradually disappear from the sky and the summer team left — retracing their three-week-long journey by helicopter, then icebreaker, then plane from Tasmania in Australia, and eventually back to Europe — he simply bedded down. “It felt like home.”

Penguins and ‘Polies’

It was a different experience for Lauren Lipuma, an American communications specialist who summered at the much larger, U.S.-run McMurdo research base in 2021 as the sole editor of the only Antarctica-based newspaper, The Antarctic Sun. At the peak of the summer there, she says, there were just under 1,000 people at McMurdo, making it “basically a small town”. Like Verseux — who saw a collection of striking photos of the Concordia base one day and decided “I have to go there” — Lipuma had her interest piqued by chance. She met the man who previously held the editor’s position at the Antarctic Sun at a social engagement a few years before being deployed, and was taken with the idea of visiting the continent after hearing him talk about his job. When he retired, he let her know, and she put in an application that was ultimately accepted. She set out to the base in her mid-30s, having completed training with the American team that focused on building survival skills and was decidedly less intense than the training program run by their French and Italian counterparts.

Lipuma had probably the most enviable job at McMurdo, because she was tasked with accompanying scientists on their most interesting missions in order to write about them. “I got to go out with some researchers who study Adelie penguins,” she recalls. “They spend pretty much their whole time down there at a small field camp near a penguin colony.” She went on a two-day trip to observe the research, which was a highlight of her summer.

“Penguins build nests out of stones. And so they are actually really wily and they steal stones from each other,” she says, with a laugh. “They’ll go to the other penguin nest and steal stones and kind of walk around and do that. And then the other penguin gets mad.”

Another “very fun” field trip she went on was to the McMurdo Dry Valleys, the largest ice-free area of Antarctica. There, where rock valleys without snow are surrounded by mountains and frozen lakes, there is surprisingly abundant microbial life. Lipuma accompanied a group of scientists who were looking at microbes in one of those frozen lakes among the dry valleys — and in order to get to those microbes, these researchers had to learn how to scuba-dive onsite, in the most challenging conditions imaginable.

“You can imagine like how cold the water is,” she says. “It’s covered with ice, so they have to make a big hole, drill it, and then you go down there and the divers are basically in a drysuit that keeps them warm, and there’s like all sorts of cables hooked up. And I don’t know if you remember the old Scooby-Doo cartoons, but that is what it looks like: a big, metal, round helmet with a big glass plate.” Lipuma watched two young women take a little boat into the middle of the lake and then dive down, while other people on their team held thick cords attached to their suits. Deep under the surface, “they’re taking soil samples, water samples, leaving certain things down there to track chemical processes and chemical reactions,” she says. You have to be “in really good physical shape” to even attempt something like that, she adds; even simply collecting the gasoline to fuel the boats requires a lot of strength to turn the cranes in the freezing air.

Lipuma’s days were all very different from one another. Sometimes she’d go on an outing; sometimes she’d take time to write up her findings on the base. She reported on the lighthearted parts of being in Antarctica — the nicknames the crew had for various things (“When we would get shipments of fresh fruits and vegetables down, we’d call those ‘freshies’. The people who go to the South Pole are ‘Polies’”); the movie screenings and holiday plays they put on for each other, like a version of the Nutcracker themed to McMurdo or a tongue-in-cheek Olympics — and the more hard-hitting science. And she loved living with 24 hours of daylight: “It’s really great because you kind of always feel safe. At least at McMurdo, there are three or two or three bars on station, or just kind of social gathering spots, and so you can go and hang out with people, and even if you want to stay out till the middle of the night, you open the door and you can walk back to your dorm. You don’t have to be like: Oh, I’m walking in the dark.”

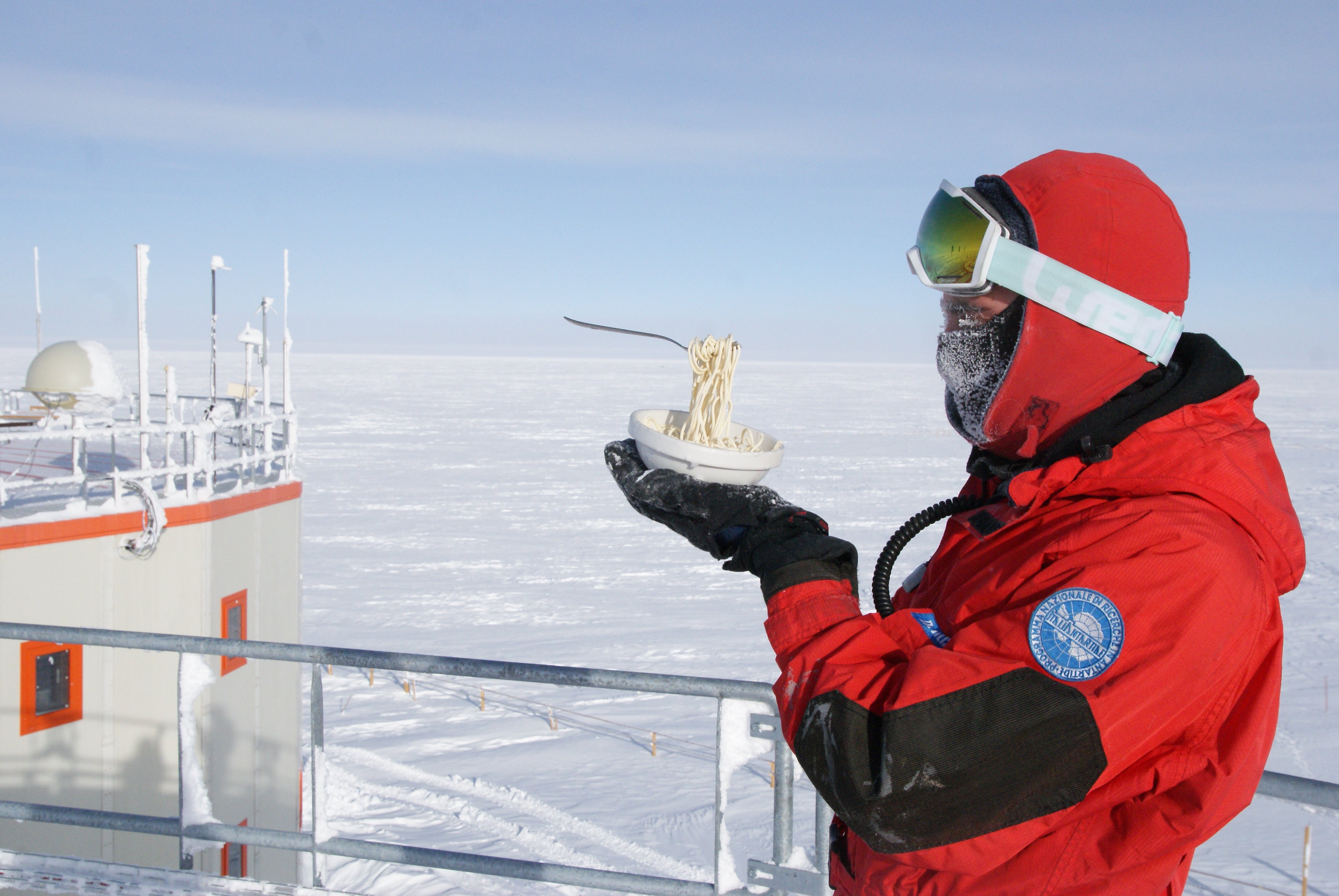

Verseux’s days, by contrast, were almost all the same. He would get up early in the morning and immediately eat as much bread as he could stomach, along with five eggs and any extra trimmings available, because his body burned so many calories to stay warm. Then he’d get dressed for the two to three hours he’d spend outside taking measurements, in multiple layers of clothing, socks, gloves, balaclavas, hats and masks. “You had a mirror next to the door where you could make sure that you have no skin exposed, because if it’s close to -112F in temperature and you have even a square centimeter exposed, and then there’s a bit of wind, your skin can freeze within seconds,” he says.

Outside in the darkness, he would emerge under “a crazy night sky, because the atmosphere is very thin and very dry. So you see the stars like nowhere else.” Alone, he would walk 700 meters from the station and take measurements in the snow and record observations on the weather. Then he would spend some time in an outpost shelter, maintaining instruments and eating chocolate and raisins to keep his energy up.

He returned to the station for meals — everyone eats lunch and dinner together, in order to keep on a proper circadian rhythm in the absence of sunlight. In the afternoons, Verseux would dedicate time to do the admin tasks expected of the station leader: making sure problems were being addressed in the right places, writing up reports, organizing equipment. Then, during their free time and their one-day weekend, the French crew members would teach their language to the Italians and vice versa. Despite the fact that they were a group of very different people, they had to work hard to foster good feeling and a positive group dynamic. Because when you’re unreachable by the rest of the world and living in a tiny research station surrounded by darkness and ice, making sure you can stand the people around you isn’t just a good idea; it’s a survival strategy.

A strange kind of addiction

Lauren Lipuma says she met a few people at McMurdo who had been coming back year after year, some of them for decades. “There are some people who joke that they can’t go back to the real world anymore,” she says. “They just don’t know how to function around a non-Antarctica environment. I mean, people really, really love it.” Some of the most committed keep coming until they’re in their seventies, at which point the possibility of ill health rules them out.

There is clearly something addictive about the “unplugged” nature of the continent, Lipuma says, and the way in which you can avoid the politics and the “drama” of everywhere else. It’s also “the most beautiful scenery you can imagine,” she adds: she wasn’t prepared to be so taken aback by the sight of the region. Nothing elsewhere on earth can compare.

“Even though it’s quite monotonous, there is an intensity of living there which you kind of miss when you are back in a city,” says Verseux. “You are living with people with whom you are going through very strong experiences and you have to solve problems together. And, you know, sometimes you are outside on the ice and it’s very intense and you feel very alive.” It’s easy to at least “somewhat miss that intensity.”

For Lipuma, however, the practical challenges of preparing to go outside each day in such unrelenting cold meant she didn’t become one of the regulars. She still remembers the moment she stepped out of the small plane that brought her to McMurdo and her snot instantly froze inside her nose. It was weird and it was incredible, she says, and she’d be happy to work in an isolated region again — but she’d rather do it somewhere a little more hospitable, weather-wise.

Verseux says he brought back “an appreciation from simple things” after returning from his year in Antarctica: being outside without having to put on a thick suit; being able to call his friends and family; eating a variety of food. Three years before he set out to Antarctica, in 2016, he’d spent a year in isolation with just five other people on a remote expanse in Hawaii, as part of a NASA-funded Mars simulation. There, in a geodesic dome with a single tiny cot for privacy and powdered cheese and canned tuna for food, he began to write.

“I found writing very useful, especially when the environment doesn’t change, when your memories tend to blend into each other,” he says. “So I started writing a blog and then books, and I’ve kept up this habit.”

Verseux’s abiding memory of Antarctica is, like Lipuma’s, the staggering beauty of the environment. “It’s like, the Milky Way seems painted and white and the moon is enough to light your path because it’ll reflect in the snow, almost like it’s glowing,” he says. “And it looks like the snow and the stars are made of the same material — the same glowy, diamond white. It’s really, really beautiful.” The beauty is otherworldly, he adds: stepping out of the prop plane that dropped him off at the station at the beginning of his year on the continent, it feels like you are “stepping onto another planet”.

And then, eventually, you return — to traffic, and news cycles, and fresh fruit. Verseux often thinks about the quiet, the clarity, and the discipline of that year. Having experienced the highs and the lows of two separate years in extreme isolation — after which he emerged into the Covid pandemic and its associated lockdowns — he says he’d happily go on a Mars mission, if given the chance.

Research is ongoing throughout the multiple stations in Antarctica. A 10-year long effort to find air bubbles in ice that’s been in place for two million years is the one that Lipuma says most fascinates her. If scientists are successful in finding them, it could tell us a huge amount about how the world’s climate has changed over a record amount of time, and potentially how we can mitigate climate disasters in the future.

Each year, a few thousand scientists continue to deploy to research stations clustered mostly around Antarctica’s coasts. Of those, only around 1,000 in total remain through the unforgiving winter. And yet, many of them come back. The appeal of such a self-imposed hardship can be hard to grasp — until someone like Verseux describes the infinite silence, the Milky Way hanging bright above the glowing snow. Then it begins to make sense. After all, Antarctica is what’s left when the niceties and complexities of the everyday fall away. Little wonder some people feel the pull to return to the only place left in the world untouched by politics and unreachable for most of the year, a place where every person has a purpose and every action has a consequence, a place where you can quietly live as the most extreme version of yourself.