“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

I was standing in my kitchen reading the Sunday New York Times on the morning of May 5, 2003. The shock headline was buried on page six: ICONIC ROCK FACE SUCCUMBS TO AGE AND HISTORY.

“Oh my God!” I overreacted, loudly.

My sons, at the breakfast table, cried out, “Dad, are you OK?”

This was just a few years after the Towers fell. Also, not long after I had survived a 99 percent blockage of the widow-maker artery in my heart. And my dad had recently, shockingly, died on his morning run.

So we were already on edge when the Great Stone Face on New Hampshire’s Cannon Mountain fell into Profile Lake.

I couldn’t tell you the first time I hiked in the White Mountains. That’s because my dad, the foundational hike leader in my life, dragged me up there the day after I learned to walk. Or maybe it was the day before. There’s a picture of me at age four or so, at the foggy timberline of Mt. Washington, looking like I’d just stopped crying or was about to start. I learned how to suffer, and be thrilled, and get dirty, on the trail from an early age, because my dad considered those to be essential life skills.

Daniel Webster and my dad had a lot in common. The great American statesman looked up at the Great Stone Face of Franconia Notch and wrote: “Shoe makers hang out a gigantic shoe; jewelers a monster watch, and the dentist hangs out a gold tooth; but up in the Mountains of New Hampshire, God Almighty has hung out a sign to show that there he makes men.”

That was my dad’s mountain mission for his four sons, as well. He was a World War II veteran, returning to a peaceful world and, with my mom, launching a big family—or a hiking party, as the case may be. As a boy in Springfield, Massachusetts, he had joined his older brothers on hikes in the Whites, and that would be our fate as well. Every 4th of July weekend my dad would awaken the four of us in the black of night, herd us into the car in Connecticut, and we’d wake up in New Hampshire. None of this “anybody wanna go for a hike?” stuff. This was mandatory outdoor education whether we liked it or not.

We learned to love it.

Most of the chatter about the so-called “Greatest Generation” centers around their difficult progression through a Depression and two world wars, and then how they shook all that off to launch the most extravagant economic boom in history. My dad was a part of all that, serving as a chief petty officer in China during WWII, getting his MBA on the GI Bill, and launching a 50-year career as an accountant for General Electric. That doesn’t sound particularly heroic, does it?

But my dad ruled our hikes with an iron whistle, like Colonel Von Trapp in the Sound of Music. One blast meant “stop,” two was “go,” three (rarely heard) signified “rest,” four was “mud in trail,” and five blasts meant “hike leader farted; hold your nose.” My strait-laced mom was happily chilling back at home—no husband or sons to watch out for—which encouraged ribald repartee on the trail. I will always remember the time when we arrived at Mizpah Hut to see a 44DD bra hoisted high on the flagpole.

I’ve been contributing to Backpacker for a long time, and published many tips here that run exactly contrary to the rules my dad enforced on the trail: No water before noon. Rest stops at rigidly controlled intervals. Ignore the weather. Push to the summit!

Compounding those risks, our crew was entirely outfitted in Chuck Taylors, blue jeans, cotton jackets, and war-surplus gear, including a pack we called “droopy drawers” for its non-ergonomic profile. As the youngest, I carried that one. It’s a wonder I survived all that hiking malpractice, much less launched a lifetime obsession with the outdoors.

My dad loved to tell the story about the day he and his sons hiked from Mizpah to Lakes of the Clouds Hut. After our bacon and cocoa breakfast–thank you, Hut Croo!–we set off on the Crawford Path under glowering skies. By the time we emerged from the krummholz, those clouds were scraping our ballcaps, the wind had accelerated, and the temperature had plunged. Time to head for cover! Except, no. We were already halfway to Lakes, my dad reasoned, so we were damned moving forward and backward. Forward it was. Always forward.

“By the time we reached Lakes,” my dad would laugh, “we were all crying!”

It’s hard to gain perspective on your own crazy childhood and the crazy people who managed it. So I rang up Kelly Davis, age 58, the Research Director at the Outdoor Industry Association, to discuss how my dad’s generation influenced those that followed. Though she now tracks Millennials and Generation Z in the backcountry, Davis, too, was raised by a Greatest Generation fighter-pilot-turned-dad and outdoor taskmaster.

“My parents weren’t even thinking about my safety outdoors,” she told me. “From the age of six I was required to have basic outdoor competency—to shoot a gun, find food and water, fall down and pick myself up again. We were out there on our own. It was uncomfortable and scary, but it was a blast!”

And she adds, almost as an afterthought: “We always made it back.”

The key, she says, was learning to ride the continuum from pleasure to discomfort, and redefine suffering in ways that keeps you exploring, having adventures. Type-two fun—defined as “fun in retrospect, but not while it’s happening”—may be miserable, but it gives you stories to tell.

This emphasis on embracing the suck, and the notion that it’s not a real adventure unless you suffer, influenced my dad, and infected me. I make hard choices in the wilderness, and they often involve bulling ahead in the face of bad weather or challenging routes. It’s not just me. Such modern avatars of thru-hiking as Cheryl Strayed have raised misery to a purification ritual.

Davis believes that this approach to the not-so-great outdoors came from my dad’s generation. She cites WWII soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division, an alpine fighting unit that was recruited from college ski teams in the northeast and trained in the high mountains near Leadville, Colorado. They fought the Germans in the Italian Alps, breaking through a Teutonic wall after scaling a 2,000-foot cliff at night, and helping to win Italy back from the Nazis. The survivors returned home to launch the U.S. ski industry, lead the Sierra Club, found Nike, and have lots of babies, among other very Greatest Generation activities. And those babies approached the outdoors as if they were still at war.

My favorite 10th-Mountain accomplishment, aside from making the world safe for democracy, are the 28 backcountry huts that dot the mountaintops from Vail to Aspen, built by soldiers from the unit returning from war. Those huts were the first thing Davis mentioned when I asked what my father’s generation did right.

“Life wouldn’t be as good without them,” she told me. “We have to acknowledge that contribution, that vision.”

That generation wasn’t always the greatest, of course. In their ignorance, they stole land from Native people, made outdoor recreation a very white space, and torched the environment in the name of progress. Even John Muir, who inspired my dad, was a racist asshole, at the same time he was saving the Sierras for my eventual enjoyment.

That birth cohort went both ways, just like the Crawford Path.

I applied to Bates College, in Maine, in part because it was just an hour from Pinkham Notch. I double-majored in English and Outing Club, and I still can’t tell you which was more useful.

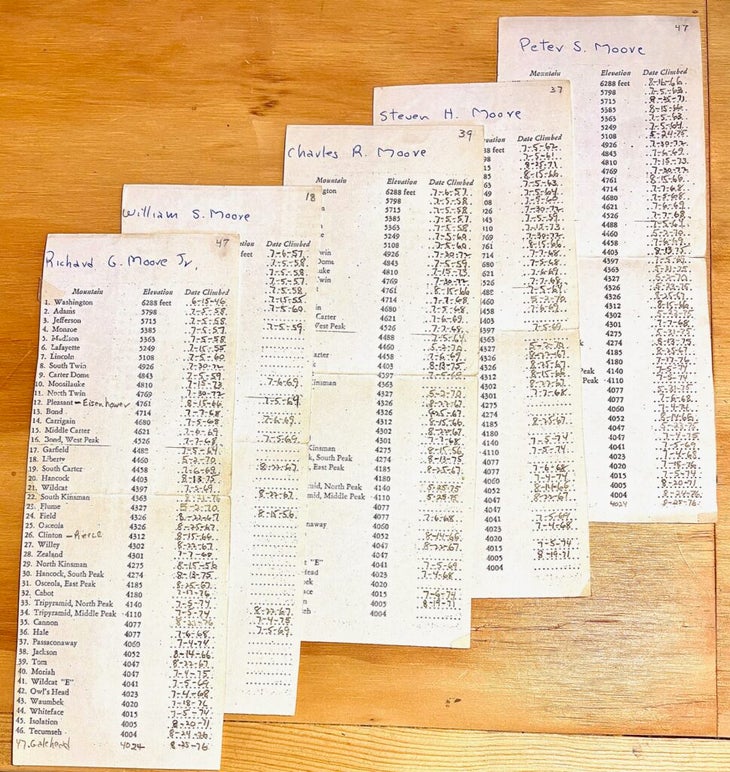

During the summer after my junior year, I saw my dad studying his list of New Hampshire’s 4,000-footers. “I’m not sure we ever reached the summit of Mt. Galehead,” he told me, ominously. That 4,042-foot-high peak had been added to the list in 1967, when an updated quadrangle was released by the U.S. Geological Survey.

His observation about Galehead sounded almost guilty—as if he were admitting to looting artifacts from the Parthenon. That list of 47—no make that 48—peaks was our version of rosary beads: We clicked through them in homage to a mountain range we loved, and a hiking history we shared.

I must point out: There is zero chance that we’d missed the peak of Galehead when we hiked the Pemigewasset Traverse, four years earlier. We would have easily banged that out after climbing North and South Twin. But my dad couldn’t specifically remember it, and his accountant mind, and his sense of morality, wouldn’t let that slide.

Later that summer, we arose long before dawn and drove to New Hampshire. On the trail, we passed Galehead Hut at a near sprint because we had another destination in sight: Full, legitimate membership in the Four Thousand Footer Club of New Hampshire.

We received our acknowledgements and embroidered patches from the Appalachian Mountain Club a year later. My dad took his big hike off the planet a couple of decades after that, dying of a heart attack on his morning run. Now my Brooklynite son wears my dad’s patch on his backpack when he rides the subway.

And, we’re all still climbing, long after the original hike leader hung up his pack. For us, it’s not just a leisure activity—it’s our life force. And my dad led the way with two blasts of his whistle, signalling that, no matter what, it’s time to go.